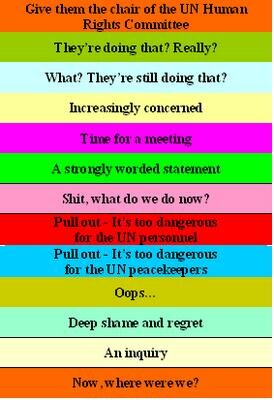

UN Color Code Alert System Update

Just a note that due to Iran’s resumption of uranium processing, the United Nations has increased its Alert System to “Increasingly Concerned“. (Graphic by Chrenkoff)

Ockham’s Razor – Since October 2001 – by Scott Kirwin

Archive for August 2005

Just a note that due to Iran’s resumption of uranium processing, the United Nations has increased its Alert System to “Increasingly Concerned“. (Graphic by Chrenkoff)

In case you don’t know, one of today’s best illusionists is Criss Angel. Criss is like a cross between Rob Zombie and Houdini, although Criss is much better looking and probably smells a whole lot better.

Criss has his own show on A&E, and it’s 30 minutes of some of the best magic you’ll find outside of New York. In fact, he had a show that was one of NYC’s best attractions.

Just one thing: He really needs to stop scaring the bejeezus out of his mom. If he were my kid, I’d slap the crap out of him for making his momma cry.

Just a note that Gene Mauch died of cancer today at the age of 79.

If you don’t know who he is, suffice it to say that he was one of baseball’s legendary managers. Here’s a great piece on him. HatTip: Powerline.

Posted at Dean’s World here.

Normally I don’t link to Instapundit because… well… doing so is redundant since most of us read the thing.

That said, Michael Totten, writing while Reynolds is on vacation, writes about the troubles with the Democratic party and then ends:

Plenty of socially liberal people voted for George W. Bush on national security grounds. Some of us would go home again if we could.

On the other hand, some of us wouldn’t. I broke with the Democratic Party after Sept. 11, 2001, when the President prepared for war in Afghanistan and the anti-war Left summoned Jimmy Carter, Michael Moore and Ted Kennedy from the 9th Circle of Hell. The Democratic lurch to the Left after 9-11 was so hard, so anti-populist, that it got me to thinking deeply about what that party means and why it exists.

I grew up as a Democrat. My parents spent the Depression trying to survive, and as late as 1954 they were still making decisions about who got fed and who didn’t (my parents skipped meals so that the kids didn’t have to). FDR was viewed not as just a president, but as a kind of savior of the family since my father did CCC and WPA work. JFK was the first American Saint for Irish-American catholics, and I still remember his portrait next to and just slightly below the painting of the Virgin Mary. My dad was blue collar – and union – and even though his kids got educations and became white collar, I don’t think we’ve ever crossed a picket line.

However, thinking back, after Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in ‘68 the Democratic Party and my parent’s view of it seemed to change. Sure we voted straight tickets, but we did more in homage to the party of Kennedy than support of its policies.

9-11 changed all that. I realized that there was one issue that trumped all others: war.

I realized that there were people who were happy to kill me and my family simply for being Americans. I realized that these people were single-minded in their determination and so brainwashed in their beliefs thatit had to be us or them – and I will do everything to make sure we survive.

Gay rights? I believe Gays have a right not to be hung or have walls collapsed upon them. Women’s Rights? I believe that women have a right to not have to walk 3 paces behind a man in a burqa. Religious Freedom? The same nutjobs that want to kill me for being an American also dynamited 2000 year old Buddhist statues and forced Hindus to convert to Islam. Freedom of Expression? You think the PMRC was bad, the Taliban banned all forms of music.

The Democrats didn’t seem to understand this, or perhaps they did and just didn’t care. After all, they had lost power, and the further from power they got the more they entertained the likes of Michael Moore and Noam Chomsky.

After all this, do you think I consider the Democratic party my home? Do you honestly believe that there is anything they can do to “bring me back?” Dean considers Hillary Clinton; I consider her a liar of the first rank who tries to sound nationalistic but can’t help but come across like a limousine liberal in love with transnationalism.

Someone bulldozed my home and built a stripmall in its place, and when that happens you realize that you can never go home again.

Posted at Dean’s World here.

School for The Kid is closing in. The roses have been munched by Japanese Beetles (BTW the Japanese call them “American Beetles”; since they eat beautiful things and screw all day the Japanese are probably on to something there.) The garden is starting to look beaten and the days aren’t quite as long as they were last month.

Yep, it’s time for some nostalgia.

I posted this topic last year on The Razor, and thought I would put it to Dean’s much larger audience. What is your favorite dead blog? We will posit that no posts in 6 months constitutes “death”. Link if possible.

Oh, and NO USS Clueless – SDB’s blog – if only because I want some variety in the responses.

I’ll start with Zach Barbara’s Voice From the Commonwealth. I don’t know what happened to Zach: maybe the Kennedy machine is holding him hostage in a bunker under Harvard Yard. However Zach had quite the eye for issues, and his postings on “Comrade Bob” Mugabe stand as some of the best ever done on a living dictator who really, really needs to eat a bullet.

Thanks to Dean I found this blog that is tracking the rescue process closely.

Here’s the latest news...

Hang in there guys… Hang in there…

Posted at Dean’s World here.

“The inaccurate perception that global sourcing is causing a net loss in US technology jobs is a factor in some students’ decisions not to pursue higher education in IT. It is a perception that we are working to correct,” Harris Miller, president of the IT Association of America said.

Inaccurate perception? For years and the IT Association of America have joined Microsoft CEO Bill Gates to push for an unlimited number of foreign IT workers into the United States, and have fought all efforts to halt or even study the flow of jobs abroad and the potential danger this poses to American security. Today there is no limit to offshoring. Companies exhort executives to ponder “What can I outsource today?” It’s gotten to the point that Gates has warned companies that they are outsourcing too much. That hasn’t stopped the lemming-like rush to offshore.

Who wants a job where “long term” means next year and stability lasts only as long as the current pay period? Who desires a job competing against an influx of nonimmigrant visa holders who make on average 25% less than you do? How about a job that requires years of training but can be sent abroad today for a fraction of your prospective salary? Would you get a degree in a field that will have completely changed by the time you graduate? Or a job whose entry level positions have been sent abroad?

While it pains me to say this, college kids aren’t stupid. Enrollment in the Computer Sciences (CS) bachelors degree programs dropped 19% in 2004, and the number majoring in CS declined by 23% overall. Kids are voting with their feet, avoiding a field that doesn’t guarantee them a wage to pay back their student loans. Dr. Ron Hira, Assistant Professor of Public Policy at Rochester Institute of Technology and the chair for IEEE-USA Career & Workforce Policy, attributes this decline to one simple fact: a Computer Science degree doesn’t pay.

IT wages and salaries have been in decline for years in the USA, while they have been skyrocketing in India and China. Why? Because IT jobs are leaving the US and going to those nations. There is simply too large a pool of IT trained labor in the USA chasing after too few jobs available here. Meanwhile, Congress, through nonimmigrant visa programs such as the L-1 and H-1b, have allowed more than 1 1/2 million foreign workers into the United States, mostly men from China and India to fill positions in the IT field.

Forrest Research claims that 11 percent of American white-collar jobs, affecting 14 million people, are vulnerable to offshoring. The research arm of an offshoring firm says 540,000 service jobs moved offshore through 2004 and predicts a loss of 3.4 million positions by 2015 (source). In theory Globalization is supposed to be a win-win for both nations; in fact, Nobel Laureate Paul Samuelson details how offshoring to China has led to permanent per capita real income loss. Prof. Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2001, points to the decline of real wages in the United States in the 10 years after the signing of NAFTA as proof that trade with China isn’t solely to blame for this income loss.

So college students are avoiding fields that can potentially be offshored. Do you blame them? Miller, whose organization is generously supported by offshoring giants like HP, IBM and Tata, has apparently become concerned with this situation – one that he has helped create.

What’s the matter Harris, afraid you’ll run out of people to send to the unemployment line?

Oh, and before you mention the supposed benefits of offshoring jobs read this.

Tom’s Hardware has an article discussing the pioneers of gaming. In the process they mentioned one of my all time favorite video games:

Death Race

The game dates to 1976. I remember playing it onboard the SS Admiral in St. Louis, one of the coolest boats ever designed. I don’t remember much about the voyage from the Arch down to the Jefferson Barracks Bridge, but I do remember that game. It seems so primitive today, but in my imagination at the time I was David Carradine running down the bad guys.

It was almost as much fun as playing “Rollerball” on my 4-wheeled rollerskates. Yes, the 1970s were a strange decade to grow up in.

I first mentioned collecting baseball cards in this post from last December. Since that time I have continued collecting – much to the wife’s annoyance. “There is nothing more un-sexy than a man playing with his baseball cards,” she has said – so I hide my hobby from her eyes.

I have pondered why I chase after these 30+ year old pieces of paper. Today I found this review of a book about card collecting aptly named “A House of Cards“.

Bloom links this nostalgia to anxieties about deindustrialization and the rise of the civil rights, feminist, and gay rights movements. He examines the gendered nature of swap meets as well as the views of masculinity expressed by the collectors: Is the purpose of baseball card collecting to form a community of adults to reminisce or to inculcate young men with traditional masculine values? Is it to establish “connectedness” or to make money? Are collectors striving to reinforce the dominant culture or question it through their attempts to create their own meaning out of what are, in fact, mass-produced commercial artifacts?

Gendered nature of swap meets? Anxieties about deindustrialization?

Uhm. Nope.

Gendered? Is that even a word?

Gendered deindustrialization of the feminist and gay rights movements.

Does that sound like a master’s thesis in Sociology or what?

Personally the best answer I’ve found is that card collecting reminds me of my father. It also allows me to relatively cheaply fulfill some childish dreams I had as a kid. Beyond that, I couldn’t care less about gendered anything.

I grew up about a thousand miles away from the nearest ocean, but I still hope that these men can be saved.

At least this time the Russians asked immediately for help, instead of waiting until it was too late last time.

Godspeed.

Creationism special: A sceptic’s guide to intelligent design

Source: New Scientist by subscription only

ADVOCATES of intelligent design argue that it deserves to be taken seriously as a rigorous scientific alternative to evolution by natural selection. But just what is it, and is it science at all?

Intelligent design (ID) is more sophisticated than its predecessor, “creation science”, which sought to gather scientific evidence in support of the Christian creation story. By starting from a pre-conceived conclusion and selectively using evidence to back it up, creation science was clearly unscientific.

ID is different. Its supporters argue that we can use science to find evidence of a designer’s handiwork in nature, while claiming to be agnostic about exactly who the designer is. “Often people think the designer is the Big Guy in the Sky. But it doesn’t have to be that at all,” says William Dembski, a mathematician, philosopher and leading ID proponent affiliated with the Discovery Institute, a creationist think tank in Seattle. He describes ID as a scientific programme that leads to an understanding of a generic supernatural intelligence.

Like many creation scientists ID advocates are happy to accept a small role for natural selection, for example, in the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Unlike creation scientists, many of them are also willing to accept that all organisms came from a common ancestor. But that’s where advocates of ID and Darwinism part company.

The difference, says Michael Behe, a biochemist at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and a leading proponent of ID, “is that Darwinism postulates random mutations and natural selection for essentially all aspects of life. ID says that at least some parts of life did not happen randomly but through purposeful design.” Nevertheless, the arguments for the inadequacy of Darwinian evolution are nearly identical to those used unsuccessfully by traditional creationists.

Their case centres on the question of how complex structures originated. Living things are full of multi-component structures that only function if all their parts are present. The bacterial flagellum, a spinning whip-like tail, for example, is made up of 40 or more proteins; blood clotting involves the coordinated interaction of 10 different proteins.

These systems are examples of what Behe calls “irreducible complexity”, meaning that they cannot function properly without all their components. Such systems, he says, could not evolve by the accumulation of chance mutations, since partial assemblies are useless.

Dembski argues that the odds against getting complex structures from chance mutations are insurmountable. For two proteins to interact to perform some new function, for example, their shapes would have to fit together. So in principle, he says, we can calculate the probability that one protein could change by chance to fit perfectly with another. Two such studies have been done. In both cases, Dembski claims the odds were so long as to rule out an explanation based on chance events.

But these calculations are logically flawed because they focus on a single, specified outcome, says Kenneth Miller, a cell biologist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, a leading critic of ID. “It’s what statisticians call a retrospective fallacy.” It is like equating the odds of drawing two pairs in poker with the odds of drawing a particular two-pair hand – say a pair of red queens, a pair of black 10s and the ace of clubs. “By demanding a particular outcome, as opposed to a functional outcome, you stack the odds,” Miller says. What these calculations fail to recognise is that many different protein sequences can be functional. It is not uncommon for proteins in different species to vary by 80 to 90 per cent, yet still perform the same function.

The “improbability argument” also misrepresents natural selection. It is correct to say that a set of simultaneous mutations that form a complex protein structure is so unlikely as to be unfeasible, but that is not what Darwin advocated. His explanation is based on small accumulated changes that take place without a final goal. Each step must be advantageous in its own right, although biologists may not yet understand the reason behind all of them.

There is also evidence that “irreducible complexity” is an illusion. Take, for example, the bacterial flagellum with its 40 proteins. One species, the stomach bacterium Helicobacter pylori, has a flagellum with just 33 proteins – “irreducibility” reduced. More tellingly, a subset of flagellar proteins turns out to serve an entirely different function, forming a mechanism called the type III secretory system, which pathogenic bacteria use to inject toxins into their host’s cells. Similarly, jawless fish accomplish blood clotting with just six proteins instead of the full 10.

So while it is true that no biologist has worked out the precise series of events that resulted in a flagellum, that in itself is not a refutation of natural selection, says Miller. It has long been argued that natural selection works by adapting pre-existing systems for new roles. The evidence so far points to exactly this process for the flagellum.

Crucially, ID does not make testable predictions. Its prediction that we should find evidence of a designer is actually nothing of the kind, say scientists: rather, it is a catch-all that takes up anything that natural selection cannot – so far, at least – explain. Dembski admits as much in his 2004 book The Design Revolution: “To require of ID that it predict specific novel instances of design in nature is to put design in the same boat as natural laws, locating their explanatory power in an extrapolation from past experience.”

Though almost all ID advocates are professed Christians, they avoid spelling out exactly what kind of designer they have in mind. “The reason is they think the designer is God, and if they mention God then the jig is up,” says Nick Matzke, a spokesman for the National Center for Science Education (NCSE), a pro-evolution organisation based in Oakland, California. This helps ID’s supporters argue that it is not subject to the ban on teaching creationism in science classes, he says. But being vague about how the designer is supposed to operate also makes ID impossible to test.

And this is the nub of it. A scientific theory must be falsifiable in principle; it must be possible to imagine evidence that would knock it down. This is not the case for ID. So even if proponents of ID were persuaded that, say, the bacterial flagellum was indeed the product of natural selection, that would not send them packing. ID says that we should be able to find evidence of design in nature, not that every structure has been designed. So ID proponents could simply concede that natural selection operated there, and then shift their ground to another molecular structure.

ID’s appeal to supernatural forces by definition puts it outside the scope of science, says Eugenie Scott head of the NCSE. After all, saying “God did it” can never be disproved.

And that’s the point. Underlying the ID agenda is a challenge to the basis of scientific method. The infamous Wedge Strategy, written in 1999 by fellows at the Discovery Institute, bemoans the “devastating” cultural consequences of scientific materialism. It also details a 20-year plan to defeat it “and its destructive moral, cultural and political legacies”. The strategy aims “to replace materialistic explanations with the theistic understanding that nature and human beings are created by God”.

In response to the controversy that followed the document’s release on the internet, the Discovery Institute says the Wedge Strategy is merely a “fund-raising document”, and should not be portrayed as some kind of sinister master plan. “We are challenging the philosophy of scientific materialism, not science itself,” it states. But far from just redefining science, most scientists would argue that introducing the supernatural will destroy it.

Creationism special: A battle for science’s soul

Source Link: By subscription only

ON 10 July 1925, a drama was played out in a small courtroom in a Tennessee town that touched off a far-reaching ideological battle. John Scopes, a schoolteacher, was found guilty of teaching evolution (see “The monkey trial – below”). Despite the verdict, Scopes, and the wider scientific project he sought to promote, seemed at the time to have been vindicated by the backlash in the urban press against his creationist opponents.

Yet 80 years on, creationist ideas have a powerful hold in the US, and science is still under attack. US Supreme Court decisions have made it impossible to teach divine creation as science in state-funded schools. But in response, creationists have invented “intelligent design”, which they say is a scientific alternative to Darwinism (see “A sceptic’s guide to intelligent design”). ID has already affected the way science is taught and perceived in schools, museums, zoos and national parks across the US.

In the US, Kansas has long been a focus of creationist activity. In 1999 creationists on the Kansas school board had all mention of evolution deleted from its state school standards. Their decision was reversed after conservative Christian board members were defeated in elections in 2002. But more elections brought a conservative majority in November 2004, and the standards are under threat again.

This time the creationists’ proposals are “far more radical and much more dangerous”, says Keith Miller of Kansas State University, a leading pro-evolution campaigner. “They redefine science itself to include non-natural or supernatural explanations for natural phenomena.” The Kansas standards now state that science finds “natural” explanations for things. But conservatives on the board want that changed to “adequate”. They also want to define evolution as being based on an atheistic religious viewpoint. “Then they can argue that intelligent design must be included as ‘balance’,” Miller says.

In January in Dover, Pennsylvania, 9th-grade biology students were read a statement from the school board that said state standards “require students to learn about Darwin’s theory of evolution. The theory is not a fact. Gaps in the theory exist for which there is no evidence”. Intelligent design, it went on, “is an explanation for the origin of life that differs from Darwin’s view”. Fifty donated copies of an ID textbook would be kept in each science classroom. Although ID was not formally taught, students were “encouraged to keep an open mind”.

These moves are part of numerous recent efforts by fundamentalist Christians, emboldened by a permissive political climate, to discredit evolution. “As of January this year 18 pieces of legislation had been introduced in 13 states,” says Eugenie Scott, head of the National Center for Science Education in Oakland, California, which helps oppose creationist campaigns. That is twice the typical number in recent years, and it stretched from Texas and South Carolina to Ohio and New York (see Map). The legislation seeks mainly to force the teaching of ID, or at least “evidence against evolution”, in science classes.

The fight is being waged on other fronts as well. Scott counts 39 creationist “incidents” other than legislative efforts in 20 states so far this year. In June, for example, the august Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC allowed the showing of an ID film on its premises and with its unwitting endorsement. After an outcry, the endorsement was withdrawn – officials insisted that it was all a mistake, although the screening did go ahead (New Scientist, 11 June, p 4).

Also in June, a publicly funded zoo in Tulsa, Oklahoma, voted to install a display showing the six-day creation described in Genesis. The science museum in Fort Worth, Texas, decided in March not to show an IMAX film entitled Volcanoes of the Deep Sea after negative reaction to its acceptance of evolution from a trial audience. The museum changed its mind after press coverage evoked an outcry, but IMAX theatres elsewhere in the US have not screened science films with evolutionary content to avoid controversy. Since 2003 the bookstores at the Grand Canyon, part of the US National Park Service, have sold a young-Earth creationist book about the canyon, repeating the creationist assertion that it was formed by Noah’s flood.

Anti-Darwin campaigners have not won everywhere. A Georgia court ruled that stickers describing evolution as “theory not fact” must be removed from textbooks. A bill in Florida that might have allowed students to sue teachers “biased” towards evolution died. And Alaska rewrote its school science standards to emphasise evolution. But religious fundamentalists have succeeded in insinuating a general mistrust of evolution. “Creationists depict evolutionists as a cultural elite, out of touch with American society,” says Kenneth Miller of Brown University in Rhode Island.

Creationism has had less cultural impact in Europe, but in the UK some state schools are incorporating it into science classes. The English education system allows private donors to invest in the refurbishment of state-funded schools in deprived areas, in return for controls over what is taught there. Emmanuel College at Gateshead in north-east England opened in 1990, financed by millionaire car dealer and Christian fundamentalist Peter Vardy. It teaches both evolution and creationism in science classes and, school officials say, lets children make up their own minds. Little notice was taken until 2002, when Vardy proposed opening more schools. A second opened last year in Middlesbrough, and a third will open near Doncaster in September.

Last September, Serbia briefly banned the teaching of evolution in schools. It changed its mind days later after scientists and even Serbian Orthodox bishops spoke out. There was also uproar over creationism in the Netherlands. The Dutch have several sects that teach creationism in their own schools. But in May, Cees Dekker, a physicist at the Delft University of Technology published a book on ID, and persuaded education minister Maria van der Hoeven that discussion of ID might promote dialogue between religious groups. She proposed a conference in autumn, but dropped the plan after an outcry from Dutch scientists.

In Turkey there is a strong creationist movement, sparked initially by contact with US creationists. Since 1999, when Turkish professors who taught evolution were harassed and threatened, there is no longer public opposition to creationism, which is all that is presented in school texts. In another Muslim country, Pakistan, evolution is no longer taught in universities.

Fundamentalist Christianity is also sweeping Africa and Latin America. Last year Brazilian scientists protested when Rio de Janeiro’s education department started teaching creationism in religious education classes.

The fear among creationism’s critics is that a pattern is emerging that will culminate in a new wave of creationist teaching. They are worried that this will undermine science education and science’s place in society. “The politicisation of science has increased at all levels,” says Miller. “What is happening is a political effort to force a change in the content and nature of science itself.”

The monkey trial

In 1925, John Thomas Scopes was a 24-year-old physical education teacher at the secondary school in Dayton, Tennessee. He was put on trial after confessing to teaching evolution while acting as a substitute biology teacher – something Tennessee had recently made illegal. The so-called “monkey” trial became a media circus and struck a powerful chord in American society.

The reasons are still with us. Natural selection provides an explanation for the origins of living things, including humans, that depends entirely on the workings of natural laws. It says nothing about the existence, or otherwise, of God.

But to many believers in such a God, if humans are just another product of nature with no special status, then there is no need for morality. Worse, evolution with its dictum of survival of the fittest seems to encourage the unprincipled pursuit of selfishness. At the time of the Scopes trial these were not merely academic concerns. The first world war had convinced many of the brutalising effects of modernity.

Scopes lost. The newborn American Civil Liberties Union paid his $100 fine and planned to appeal to the US Supreme Court, where they hoped laws like Tennessee’s would be declared illegal. They were thwarted when the verdict was overturned on a technicality.

In Dayton, though, it appeared that Darwin had won. The anti-evolutionists and rural, religious society generally had been held up to nationwide ridicule by the urban press covering the trial. As a result there were few overt efforts to pursue such legal attacks on evolution for decades.

But for some historians Scopes was no victory for Darwinism. The prosecutor, populist politician William Jennings Bryan, was seen as speaking for the “common people”. Those people, repelled by an alien, arrogant, scientific world that seemed opposed to them and their values, developed a separate society increasingly bound to strict religious laws. Before the trial, evolution had not been an important issue for these people. Now it was. For many Americans, being in favour of evolution is still equated with being against God.

Debora MacKenzie

Technorati Profile

Hat tip: The forever hot Michelle Malkin

Death Threat Graffiti in NYC Targets Republicans

I harken back to Crocodile Dundee famous quip, “You call that a knife?”

Now that’s a knife.

Better yet, since Republicans tend to favor the 2nd Amendment – treasure perhaps being the better word – then what is the likelihood that our knife wielding Liberal thug would stand a chance against one of these?

Note that this is one of Kim Du Toit’s faves.